#41 - AI and VC Inequality

Timely recent interview with the Managing Partner of Sequoia, for anyone looking to dive deeper into the topic: Sequoia’s Roelof Botha: Why Venture Capital is Broken & How Great Companies Are Built

I got sucked into the allure of VC after getting invited to participate in a fund.

Venture has this aura of being an exclusive club where outsized returns are the norm. The only real barrier is getting in.

In the public markets anyone can buy stocks from their phone. The returns are steady, but the story you hear is that the real wealth is created long before a company goes public.

And that is true for the top tier funds because they participate in those early winners. But the way it’s told, you’d think all venture funds have equal access. They don’t. Before I spoke with people who actually knew the space, I assumed even the average fund was outperforming the market.

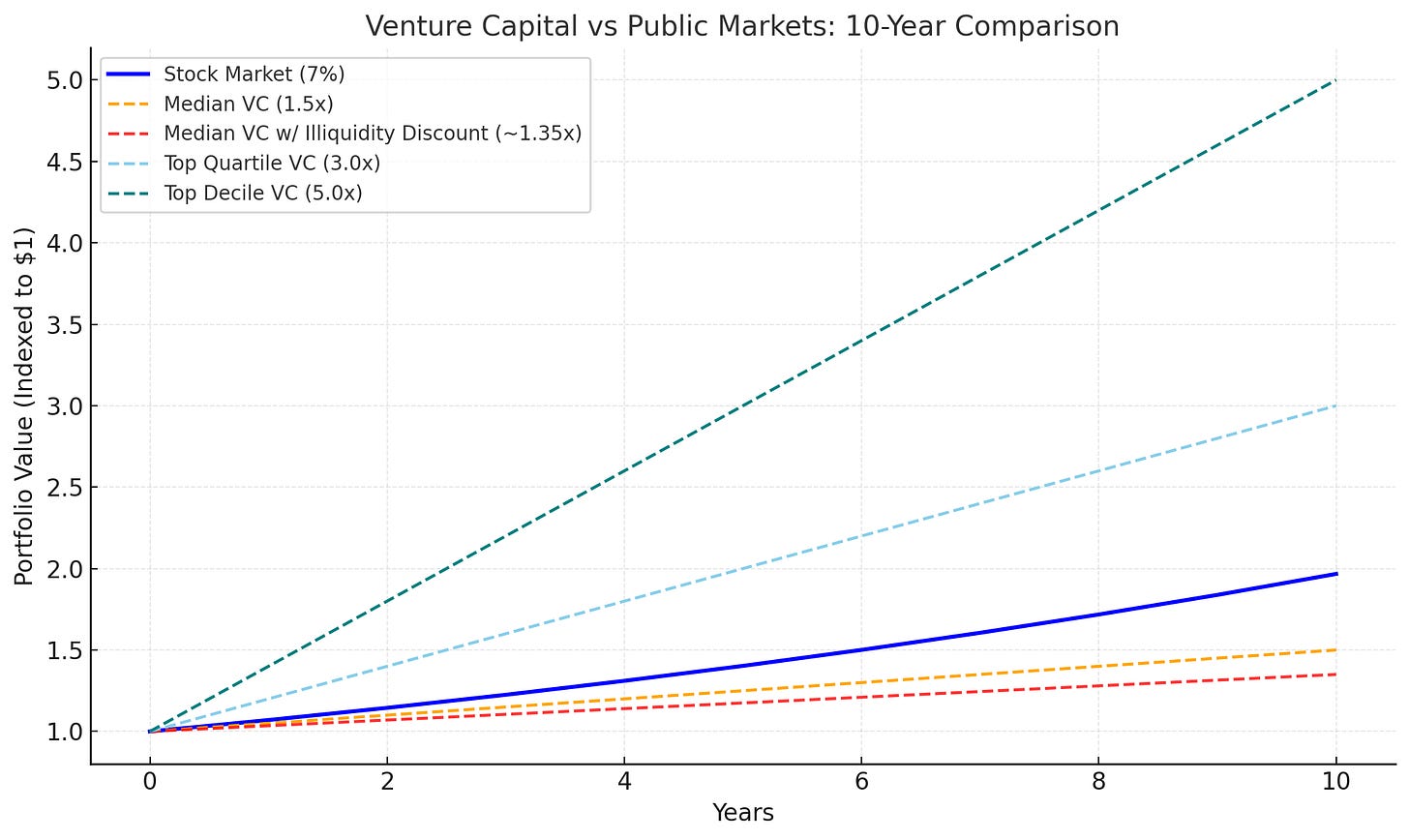

That assumption was wrong. And the data clearly tells a different story. The average venture fund does worse than a basic S&P 500 index fund. Even after ten years, and with all the illiquidity and risk, you’re likely better off in the market (see graph at the top).

In reality, the top decile funds capture almost all the gains, the median fund delivers modest returns while the bottom half destroys capital. And the reason is straightforward:

The best companies are obvious early.

They choose the top and most experienced investors.

Those investors keep winning allocations, which compounds their advantage and locks out everyone else.

Mid-tier funds are left competing for what’s left. They might back good companies, but rarely the grand slams that drive venture’s return profile.

The AI Era and Fund Inequality

In previous tech waves (social, SaaS, mobile) value creation was spread across hundreds of companies.

AI feels different. Most of the seismic value will concentrate in a few large language model providers like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Perplexity, along with the hyperscalers and chip companies that power them, such as Google, Microsoft, and NVIDIA.

The capital and data required to build these models create a massive moat and a high barrier to entry for anyone trying to start now (e.g. Meta). As the models become more tailored to individual users, the lock-in becomes even stronger.

There is also far less value at the application layer. If you build a wrapper around one of these models, the value still sits with the model itself. And as these tools become ubiquitous, most people will realize it is easier and cheaper to accomplish what they need directly through the LLM rather than through a thin layer on top.

Instead of hundreds of unicorns, we may see only a few dozen companies that matter.

Early-Stage VC Is Being Disrupted

Before AI, getting an idea off the ground required real capital. You needed a small team of engineers to build a first version, bring it to market, and iterate until you found product-market fit.

At that stage, investors were betting on the founder’s ability to create new demand, not just capture existing demand. That’s where outsized returns come from, but it takes time, capital, and a willingness to accept that most of these bets fail.

AI changes that. The tools now exist for early experimentation to happen fast and cheap. What once took quarters or even years can now be done in a weekend by a non-technical founder.

Someone can spot a problem, build a solution, and test it with real users in days.

The tradeoff is that it’s easier to copy. Fewer moats exist. But if you can capture a small slice of a market, bootstrapped and with high margins, you can build a solid six- or seven-figure business that gives you freedom and control.

Because that outcome is now more achievable, and the odds of creating generational wealth are smaller, more founders will choose it. They’ll focus on building sustainable, cash-flowing businesses to maximize both profit and time without having to deal with all the nonsense that comes with taking on outside capital.

At the other extreme, the only true grand slams will be the foundational LLM providers. The platforms everything else runs on. There will be some winners at the application layer, but far less capital will be required to reach them.

That means there are now fewer scraps for the average venture fund to fight over. The concentration of value will continue to move toward the few firms already backing the biggest players. The gap between the haves and have-nots in venture will become even wider.

Not sure if you could tell already, but I decided not to invest.

Interesting. What makes these best companies 'obvious early'?